Territorial Sea - Meaning, Breadth and the Rights of States

Introduction Territorial sea is that part of the sea which is adjacent to the coastal State and which is bounded by the high seas on its outer edge. The Coastal State exercises its sovereignty over this area as it exercises over its internal waters. The sovereignty extends to the airspace over the territorial sea as well as its… Read More »

Introduction Territorial sea is that part of the sea which is adjacent to the coastal State and which is bounded by the high seas on its outer edge. The Coastal State exercises its sovereignty over this area as it exercises over its internal waters. The sovereignty extends to the airspace over the territorial sea as well as its bed and sub-soil. This sovereignty accrues to a State under the customary international law which no State can refuse. However, the sovereignty over this area has to...

Introduction

Territorial sea is that part of the sea which is adjacent to the coastal State and which is bounded by the high seas on its outer edge. The Coastal State exercises its sovereignty over this area as it exercises over its internal waters. The sovereignty extends to the airspace over the territorial sea as well as its bed and sub-soil. This sovereignty accrues to a State under the customary international law which no State can refuse.

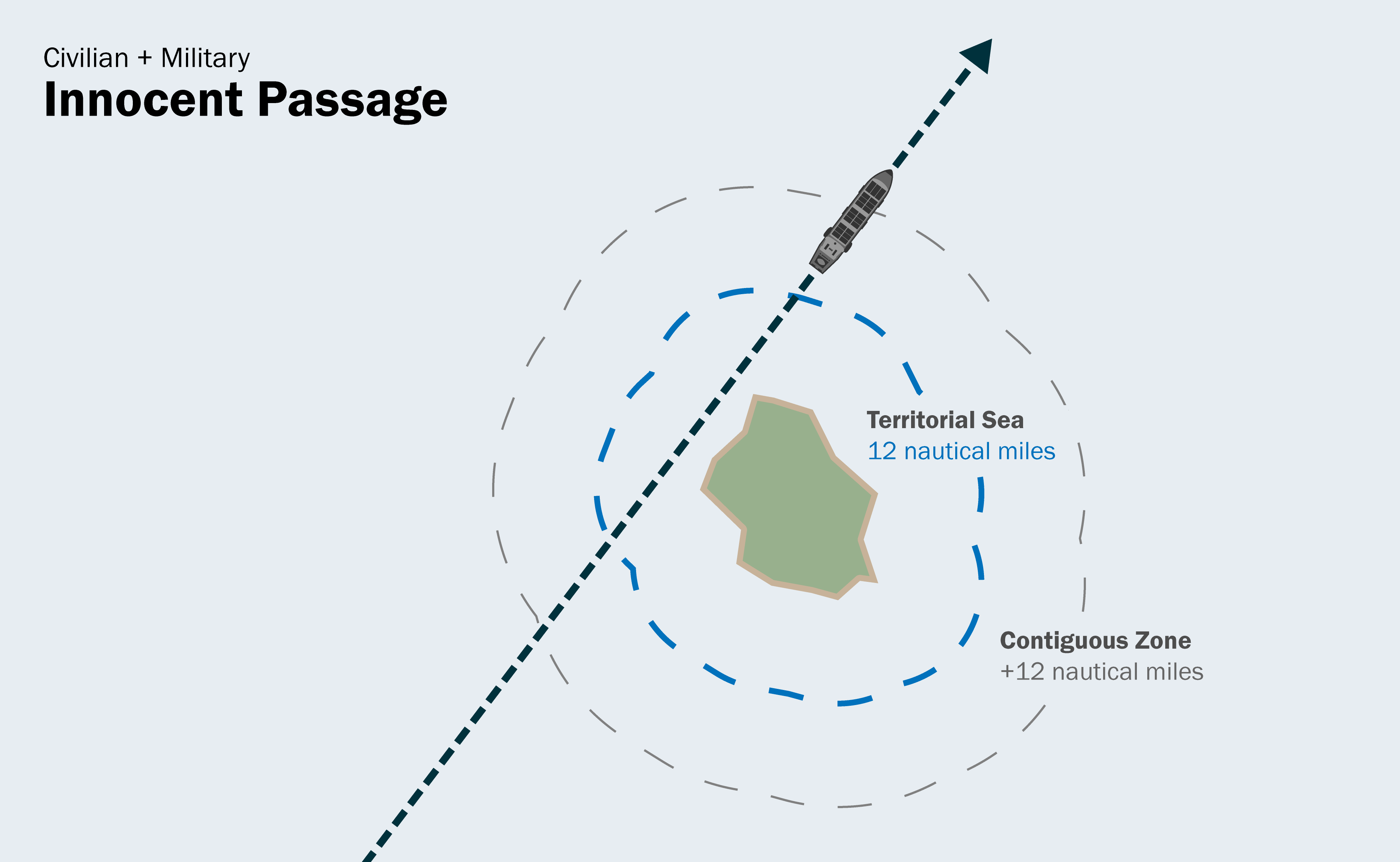

However, the sovereignty over this area has to be exercised subject to the provisions of the conventions and ‘to other rules of international law’, which provides certain rights to other States, particularly right of ‘innocent passage’ in the territorial waters of the State.

Breadth of the Territorial Sea

The breadth of the territorial sea has remained a thorny issue, and up to the 18th century, the opinion was, that breadth of the territorial sea extends to the range of a cannon shot which at that time was three nautical miles. The three-mile rule, popularly known as ‘cannon-shot’ rule as propounded by the Dutch jurist Bynkershock, had a rationale that a State’s sovereignty extended to the sea as far as a canon or fire could reach.

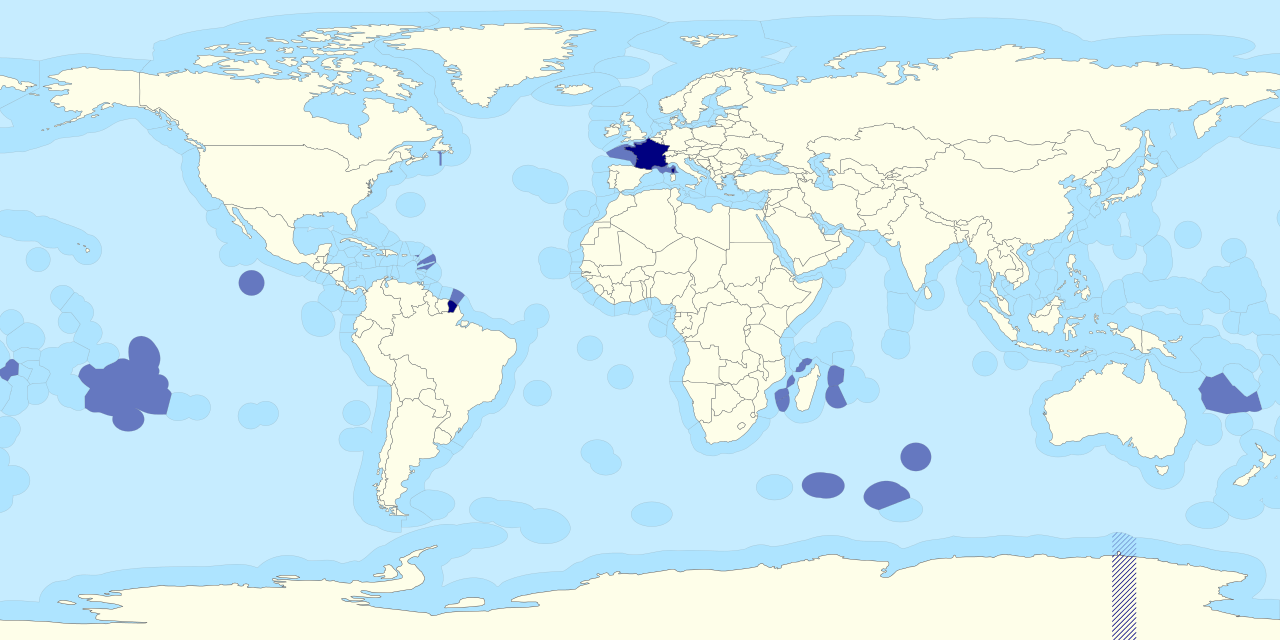

Before the 1982 Sea Convention was concluded, States proclaimed varying breadth of the territorial sea, generally ranging from 3 to 12 miles, though in certain cases they had proclaimed wider areas than that, in few cases up to 200 nautical miles. But at the UNCLOS-III, claims wider than 12 miles did not find favour and the 12 miles rule was accepted by the Conference, which may be considered the present customary international law position.

Article 3 of the 1982 Sea Convention limits the breadth of the territorial sea to 12 nautical miles ‘measured from baselines determined in accordance with the Convention’. Two methods have been laid down for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea: the low-water line and the straight baseline. The normal method used is the low-water line as marked on large-scale charts officially recognized by coastal State. Where the coastline is deeply intended and cut into, or if there is a fringe of islands along the coast in its immediate vicinity, the straight baseline method joining appropriate points may be employed in drawing the baseline from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.

The method of straight baseline was enunciated by the Anglo Norwegian Fisheries case, which had a decisive effect on the baseline issue. In this case, Norway which has a fringe coastline, by its 1935 Decree proclaimed exclusive fishery zone (meant territorial sea) along almost 1000 miles of its coastline.

The zone which was four miles wide, measured not from the low-water mark but from straight baselines linking some 48 outermost points of island and lands, at a considerable distance from the coast By using the straight baselines, some of which was 30 miles long and the longest was 44 miles, Norway could enclose waters within its territorial sea that would have been the high seas, and hence open to foreign fishing.

The UK, whose fishing interests were affected by this Decree, challenged the legality of the straight baseline system adopted by Norway and the choice of certain baselines used in applying it. The Court upheld the method applied by Norway in drawing the baselines and it also did not reject the criterion of the low water mark. But the manner of application of straight baselines is ‘dictated by geographical realities’.

It was propounded by the judgment that where a State has a rugged coastline, deeply indented, or if there is a fringe of islands in the immediate vicinity, the straight baseline, joining the low water at appropriate points, is admissible, provided:

- the drawing of baseline must not depart to any appreciable extent from the ‘general direction’ of the coast;

- the areas lying within the baselines are sufficiently closely linked to the adjacent land domain; and

- the economic interests as evidenced by long-established usage, peculiar to a particular region concerned, must be taken into account before the straight baseline method is allowed to be followed by coastal State.

The principles laid down in the Fisheries case relating to straight baselines are to be followed in drawing baselines except those of low-tide elevations, unless the lines drawn in such circumstances have received ‘general international recognition’. The system of straight baselines is not to be applied in a manner as to cut off the territorial sea or an EEZ of another State from the high seas.

The delimitation of the territorial sea between two States opposite or adjacent to each other can take place in accordance with an agreement between them, failing which the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States, is measured. This rule is not applicable in the cases of ‘historic title’ or other special circumstances.

Rights of Coastal States

The sovereignty of the coastal states extends to the territorial sea. Consequently, they have complete dominion over this part of the sea except that of the right of innocent passage and of transit by vessels of all nations. It follows from the regime of sovereignty that the coastal state has the exclusive right to appropriate the natural products of the territorial sea, including the right of fisheries therein, and to the resources of the sea-bed and its sub-soil namely, sedentary fisheries and non-living resources such as hydrocarbons and minerals. The coastal areas may enact laws and regulations.

Rights of Other States

It is the customary rule of International law that the territorial sea is open to merchant vessels of all the states for navigation. Such vessels have the right to innocent passage through the territorial sea of a state. Thus every State has the right to demand that in times of peace.

This is a corollary of the freedom of the open sea. This rule was incorporated in the Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone of 1958 under Article 14. The same provision has been laid down under Article 17 of the Convention of 1982.

Innocent Passage

The customary international law recognizes the right of innocent passage for ships of all States through the territorial waters of a State but no such right exists for aircraft in the airspace over the territorial waters. ‘Ships of all States, whether coastal or not, shall enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea.’ No right of innocent passage exists through internal waters. The passage to be considered innocent, of foreign fishing vessels, their conduct should be according to the laws and regulations made by the coastal State for fishing purposes in the territorial sea.

Under the Convention vessels entitled to innocent passage are ‘ships of all states’ without making a distinction between a merchant, public or warships. The submarines, however, are required to navigate on the surface. Warships have the right of passage through international straits, as decided in the Corfu Channel case.

The coastal States has the right to make laws to regulate the territorial waters. It can adopt laws and regulations governing innocent passage, and to prevent passage which is not innocent. Foreign ships in the innocent passage are required to comply with all such laws and regulations, framed by the coastal State, and other common international regulations for the prevention of collisions at sea.

The coastal State is required not to hamper or impair innocent passage or to apply rules and regulations in this regard in a discriminatory manner. Nevertheless, the coastal State is empowered to ‘take the necessary steps’ to prevent non-innocent passage.

The coastal State is required not to hamper or impair innocent passage or to apply rules and regulations in this regard in a discriminatory manner. Nevertheless, the coastal State is empowered to ‘take the necessary steps’ to prevent non-innocent passage.

Indian Position on Territorial Sea

India’s position in relation to the law of the sea is generally governed by Article 297 of the Constitution of India, and the Territorial Water, Continental Shelf, EEZ and other Maritime Zones Acts. The Maritime Zones Act proclaims the sovereignty of India over the territorial waters of India and the seabed and sub-soil underlying and the airspace over such water.

The limit of the territorial is the line every point of which is at a distance of 12 nautical miles from the nearest point of the appropriate baseline. All foreign ships are given the right of innocent passage through the territorial waters. The passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of India.

However, foreign warships, including submarines and other underwater vehicles, may enter or pass through the territorial water by giving prior notification to the Central Government. Submarines and other underwater vehicles are to navigate on the surface and show their flags when passing through such waters. The Central Government, if satisfied that it is necessary in the interest of peace, good order or security of India or any part thereof, may suspend the innocent passage, absolutely or subject to certain exceptions or modifications, by notification made in the official gazette. Thus, the position of India in this regard is in accordance with the 1982 Convention.

References

- Dr. H.O. Agarwal, International Law, 21st Edition, 2016

- http://nbaindia.org

- http://www.un.org

Mayank Shekhar

Mayank is an alumnus of the prestigious Faculty of Law, Delhi University. Under his leadership, Legal Bites has been researching and developing resources through blogging, educational resources, competitions, and seminars.